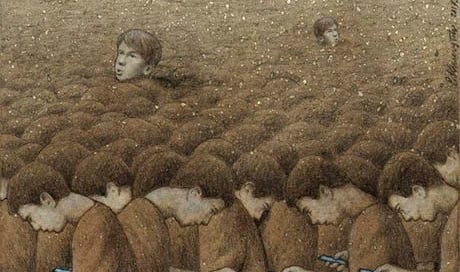

The relationship of the group to the individual is the central theme constant throughout the Douglas Social Credit story. The question as to how the individual may reap the benefits of group activity without him becoming dominated by the group is the problem which Douglas sought to unravel.

The objective of Douglas’ economic proposals is to grant to each individual the freedom of association. That is the power of the individual to choose what they will or will not support with their time and energy. The problem is that while it is true we are free to quit our jobs if we like, for most of us, the penalty for doing so is financial hardship or having to immediately resume something similar to that which we were, in quitting, trying to get away from.

At the moment many of us are coerced by the economic system into supporting activities for an income, with secondary importance given to the quality of contribution that we make through our work. At the same time, much of the necessary work that contributes so significantly to human well-being — the raising of families, voluntary community service, self-education, physical and mental nourishment, care for the sick and tired — is being edged out by expanding financial commitments in a vicious cycle of social deterioration.

Platitudes about duty aside, we must acknowledge that in the main people submit to economic associations for their own benefit. The actual activity performed is, so far as individuals are concerned, a less important factor. Because the money paid for work is more important to the individual than the job done, it is inevitable that people will persist with a bad job for the sake of the monetary reward. In this way commercial activity is able to, and increasingly does, bypass moral concerns effective in other areas of peoples’ lives.

It is a dangerous system that places large numbers of individuals in positions whereby their physical needs can only be satisfied by periodic payment so long as they unquestioningly do as they are told by increasingly distant and indifferent authority.

Fundamentally what we are talking about here is the tension which exists between the individual and the group. It is undeniable that there is great advantage to be gained by people associating in groups. For instance, the modern productive system is a cooperative venture that enables people in association to get the necessities of life in a fraction of the time time and energy it would take to secure these things on their own. But, so far as the individual is concerned, the advantages of associating in groups for economic purposes are reduced to nothing if the conditions of work, or the time it demands, does not endow greater freedom personally.

In Social Credit, first published in 1924, Douglas summarised the policy of the hidden government, which controls money to administer a system of rewards and punishments, as simply the treatment of individuality as subordinate to the group. “The appeal” he said, “is away from the conscious-reasoning individual, to the unconscious herd instinct.” Douglas focuses in on the practical result of this in his chapter on The Relation of the Group to the Individual:

The shifting of emphasis from the individual to the group, which is involved in collectivism, logically involves the shifting of responsibility for action. For instance, the individual killing of one man by another we term murder. But collective killing, we dignify by the name of war, and we specifically absolve the individual from the consequences of any acts which are committed under the orders of a superior officer.1

But if we keep in mind that we live in a world that does not necessarily conform to the intentions good or otherwise of superior officers, captains of industry, politicians etc. and “that over every place of action with which we are acquainted, action and reaction are equal, opposite, and wholly automatic” then we will see the danger of such an approach to human organisation. To return to Douglas’ example of war, while “there “may be, ex-hypothesi, no moral guilt attributable to the individual who goes to to war; the effect of intercepting the line of flight of a high-speed bullet will be found to be exactly the same whether it is fired by a national or private opponent.”2

The widespread absorption of the individual into the group and the consequent suspension of individual reason and responsibility occurs at every level. At a school where I worked I was once told by the head of the health and physical education faculty that he would do his job standing on his head if he was told to. the implication being that the following of orders would, by a very long distance, take priority over the efficient performance of his teaching duties. Needless to say he would not have considered carrying out his own business inverted.

The financial system makes money the prime consideration of human organisation. The prioritising of this external and highly manipulated medium amounts to negligence of the causal nature of the universe. We must recalibrate the financial mechanism so that it allows for the building of society on the only legitimate basis that exists —the satisfaction of the individual.

The practical remedies of Douglas Social Credit, consisting of the national dividend and the compensated price, would not only take the friction out of the economic machine, it would ultimately provide people with the power to exercise their judgement about what projects are worthy of their support. All sorts of activity that persist because they provide employment would suddenly have to justify themselves on more than just financial grounds. Surely it would be an advance if the financial mechanism could be made to support the individual in bringing their standards of common decency and sense into the economic sphere. The present state of affairs that sees the money our society requires to carry out its business inadequately dispensed for the purpose of providing a tiny minority with extravagant profits and power is ludicrously illogical and unbalanced.

Douglas once said that the fundamental objection to slavery was not bad treatment, but that it deprived slaves of control over their own policy. For most people the economic order amounts to the same thing. Conversely, the democratic idea asserts that free choice at the individual level should be the operative force in shaping society. Douglas defined liberty as the “freedom to choose or refuse one thing at a time.” If we accept this definition we cannot say we enjoy a state of liberty while we are forced to trade our personal judgement for economic security. The freedom to choose our associations without fear is the why of the economic proposals of Douglas Social Credit.

Douglas, C.H. 1924. Social Credit. Eyre and Spottiswoode, London.

Ibid.